A Quick Primer on Instrumental Variables

Outline

- Assessing Selection on Unobservables

- Basics of Instrumental Variables

- Testing IV Assumptions

- Interpreting IV Results

- Common IV Designs Today

Assessing Selection on Unobservables

- Say we estimate a regression like \[y_{i} = \delta D_{i} + \beta_{1} x_{1i} + \varepsilon_{i}\]

- But we are concerned that the “true” specification is \[y_{i} = \delta D_{i} + \beta_{1} x_{1i} + \beta_{2} x_{2i} + \varepsilon_{i}\]

- Idea: Extending the work of Altonji and others, Oster (2019) aims to decompose outome into a treatment effect (\(\delta\)), observed controls (\(x_{1}\)), unobserved controls (\(x_{2i}\)), and iid error

Oster (2019)

Key assumption: Selection on observables is informative about selection on unobservables

- What is the maximum \(R^2\) value we could obtain if we observed \(x_{2}\)? Call this \(R_{\text{max}}^{2}\) (naturally bounded above by 1, but likely smaller)

- What is the degree of selection on observed variables relative to unobserved variables? Denote the proportional relationship as \(\rho\) such that: \[\rho \times \frac{Cov(x_{1},D)}{Var(x_{1})} = \frac{Cov(x_{2},D)}{Var(x_{2})}.\]

Oster (2019)

- Under an “equal relative contributions” assumption, we can write:

\[\delta^{*} \approx \hat{\delta}_{D,x_{1}} - \rho \times \left[\hat{\delta}_{D} - \hat{\delta}_{D,x_{1}}\right] \times \frac{R_{\text{max}}^{2} - R_{D,x_{1}}^{2}}{R_{D,x_{1}}^{2} - R_{x_{1}}^{2}} \xrightarrow{p} \delta.\]

- Consider a range of \(R^{2}_{\text{max}}\) and \(\rho\) to bound the estimated treatment effect,

\[\left[ \hat{\delta}_{D,x_{1}}, \delta^{*}(\bar{R}^{2}_{max}, \rho) \right]\]

Augmented regression (somewhat out of place here)

- Oster (2019) and similar papers can say something about how bad selection on unobservables would need to be

- But what kind of “improvement” do we really get in practice?

- Original test from Hausman (1978) not specific to endogeneity, just a general misspecification test

- Compare estimates from one estimator (efficient under the null) to another estimator that is consistent but inefficient under the null

- In IV context, also known as Durbin-Wu-Hausman test, due to the series of papers pre-dating Hausman (1978), including Durbin and Wu in the 1950s

- Easily implemented as an “artificial” or “augmented” regression

- We want to estimate \(y=\beta_{1}x_{1} + \beta_{2}x_{2} + \varepsilon\), with exogenous variables \(x_{1}\), endogenous variables \(x_{2}\), and instruments \(z\)

- Regress each of the variables in \(x_{2}\) on \(x_{1}\) and \(z\) and form residuals, \(\hat{v}\), \(x_{2} = \lambda_{x} x_{1} + \lambda_{z} z + v\)

- Include \(\hat{v}\) in the standard OLS regression of \(y\) on \(x_{1}\), \(x_{2}\), and \(\hat{v}\).

- Test \(H_{0}: \beta_{\hat{v}} = 0\). Rejection implies OLS is inconsistent.

Intuition: Only way for \(x_{2}\) to be correlated with \(\varepsilon\) is through \(v\), assuming \(z\) is a “good” instrument

Summary

- Do we have an endogeneity problem?

- Effects easily overcome by small selection on unobservables?

- Clear reverse causality problem?

- What can we do about it?

- Matching, weighting, regression? Only for selection on observables

- DD, RD, differences in discontinuities? Specific designs and settings

- Instrumental variables?

Instrumental Variables

What is instrumental variables

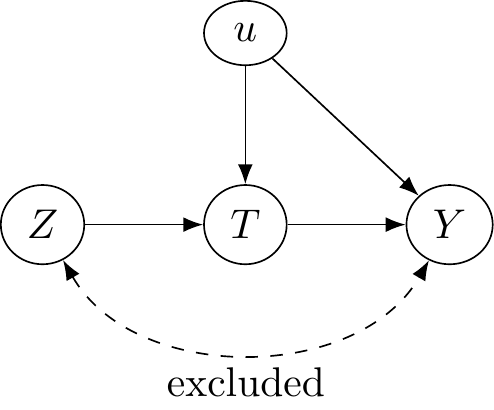

Instrumental Variables (IV) is a way to identify causal effects using variation in treatment particpation that is due to an exogenous variable that is only related to the outcome through treatment.

Simple example

\(y = \beta x + \varepsilon (x)\), where \(\varepsilon(x)\) reflects the dependence between our observed variable and the error term.

Simple OLS will yield \(\frac{dy}{dx} = \beta + \frac{d\varepsilon}{dx} \neq \beta\)

What does IV do?

- The regression we want to do: \[y_{i} = \alpha + \delta D_{i} + \gamma A_{i} + \epsilon_{i},\] where \(D_{i}\) is treatment (think of schooling for now) and \(A_{i}\) is something like ability.

- \(A_{i}\) is unobserved, so instead we run, \(y_{i} = \alpha + \beta D_{i} + \epsilon_{i}\)

- From this “short” regression, we don’t actually estimate \(\delta\). Instead, we get an estimate of \[\beta = \delta + \lambda_{ds}\gamma \neq \delta,\] where \(\lambda_{ds}\) is the coefficient of a regression of \(A_{i}\) on \(D_{i}\).

Intuition

IV will recover the “long” regression without observing underlying ability

IF our IV satisfies all of the necessary assumptions.

More formally

- We want to estimate \[E[Y_{i} | D_{i}=1] - E[Y_{i} | D_{i}=0]\]

- With instrument \(Z_{i}\) that satisfies relevant assumptions, we can estimate this as \[E[Y_{i} | D_{i}=1] - E[Y_{i} | D_{i}=0] = \frac{E[Y_{i} | Z_{i}=1] - E[Y_{i} | Z_{i}=0]}{E[D_{i} | Z_{i}=1] - E[D_{i} | Z_{i}=0]}\]

- In words, this is effect of the instrument on the outcome (“reduced form”) divided by the effect of the instrument on treatment (“first stage”)

Derivation

Recall “long” regression: \(Y=\alpha + \delta S + \gamma A + \epsilon\).

\[\begin{align} COV(Y,Z) & = E[YZ] - E[Y] E[Z] \\ & = E[(\alpha + \delta S + \gamma A + \epsilon)\times Z] - E[\alpha + \delta S + \gamma A + \epsilon)]E[Z] \\ & = \alpha E[Z] + \delta E[SZ] + \gamma E[AZ] + E[\epsilon Z] \\ & \hspace{.2in} - \alpha E[Z] - \delta E[S]E[Z] - \gamma E[A] E[Z] - E[\epsilon]E[Z] \\ & = \delta (E[SZ] - E[S] E[Z]) + \gamma (E[AZ] - E[A] E[Z]) \\ & \hspace{.2in} + E[\epsilon Z] - E[\epsilon] E[Z] \\ & = \delta C(S,Z) + \gamma C(A,Z) + C(\epsilon, Z) \end{align}\]

Derivation

Working from \(COV(Y,Z) = \delta COV(S,Z) + \gamma COV(A,Z) + COV(\epsilon,Z)\), we find

\[\delta = \frac{COV(Y,Z)}{COV(S,Z)}\]

if \(COV(A,Z)=COV(\epsilon, Z)=0\)

IVs in practice

Easy to think of in terms of randomized controlled trial…

| Measure | Offered Seat | Not Offered Seat | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Score | -0.003 | -0.358 | 0.355 |

| % Enrolled | 0.787 | 0.046 | 0.741 |

| Effect | 0.48 |

Angrist et al., 2012. “Who Benefits from KIPP?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management.

What is IV really doing

Think of IV as two-steps:

- Isolate variation due to the instrument only (not due to endogenous stuff)

- Estimate effect on outcome using only this source of variation

In regression terms

Interested in estimating \(\delta\) from \(y_{i} = \alpha + \beta x_{i} + \delta D_{i} + \varepsilon_{i}\), but \(D_{i}\) is endogenous (no pure “selection on observables”).

Step 1: With instrument \(Z_{i}\), we can regress \(D_{i}\) on \(Z_{i}\) and \(x_{i}\), \[D_{i} = \lambda + \theta Z_{i} + \kappa x_{i} + \nu,\] and form prediction \(\hat{D}_{i}\).

Step 2: Regress \(y_{i}\) on \(x_{i}\) and \(\hat{D}_{i}\), \[y_{i} = \alpha + \beta x_{i} + \delta \hat{D}_{i} + \xi_{i}\]

Derivation

Recall \(\hat{\theta}=\frac{C(Z,S)}{V(Z)}\), or \(\hat{\theta}V(Z) = C(S,Z)\). Then:

\[\begin{align} \hat{\delta} & = \frac{COV(Y,Z)}{COV(S,Z)} \\ & = \frac{\hat{\theta}C(Y,Z)}{\hat{\theta}C(S,Z)} = \frac{\hat{\theta}C(Y,Z)}{\hat{\theta}^{2}V(Z)} \\ & = \frac{C(\hat{\theta}Z,Y)}{V(\hat{\theta}Z)} = \frac{C(\hat{S},Y)}{V(\hat{S})} \end{align}\]

Animation for IV

R Code

df <- data.frame(Z = as.integer(1:200>100),

W = rnorm(200)) %>%

mutate(X = .5+2*W +2*Z+ rnorm(200)) %>%

mutate(Y = -X + 4*W + 1 + rnorm(200),time="1") %>%

group_by(Z) %>%

mutate(mean_X=mean(X),mean_Y=mean(Y),YL=NA,XL=NA) %>%

ungroup()

#Calculate correlations

before_cor <- paste("1. Start with raw data. Correlation between X and Y: ",round(cor(df$X,df$Y),3),sep='')

afterlab <- '6. Draw a line between the points. The slope is the effect of X on Y.'

dffull <- rbind(

#Step 1: Raw data only

df %>% mutate(mean_X=NA,mean_Y=NA,time=before_cor),

#Step 2: Add x-lines

df %>% mutate(mean_Y=NA,time='2. Figure out what differences in X are explained by Z'),

#Step 3: X de-meaned

df %>% mutate(X = mean_X,mean_Y=NA,time="3. Remove everything in X not explained by Z"),

#Step 4: Remove X lines, add Y

df %>% mutate(X = mean_X,mean_X=NA,time="4. Figure out what differences in Y are explained by Z"),

#Step 5: Y de-meaned

df %>% mutate(X = mean_X,Y = mean_Y,mean_X=NA,time="5. Remove everything in Y not explained by Z"),

#Step 6: Raw demeaned data only

df %>% mutate(X = mean_X,Y =mean_Y,mean_X=NA,mean_Y=NA,YL=mean_Y,XL=mean_X,time=afterlab))

#Get line segments

endpts <- df %>%

group_by(Z) %>%

summarize(mean_X=mean(mean_X),mean_Y=mean(mean_Y))

p <- ggplot(dffull,aes(y=Y,x=X,color=as.factor(Z)))+geom_point()+

geom_vline(aes(xintercept=mean_X,color=as.factor(Z)))+

geom_hline(aes(yintercept=mean_Y,color=as.factor(Z)))+

guides(color=guide_legend(title="Z"))+

geom_segment(aes(x=ifelse(time==afterlab,endpts$mean_X[1],NA),

y=endpts$mean_Y[1],xend=endpts$mean_X[2],

yend=endpts$mean_Y[2]),size=1,color='blue')+

scale_color_colorblind()+

labs(title = 'The Relationship between Y and X, With Binary Z as an Instrumental Variable \n{next_state}')+

transition_states(time,transition_length=c(6,16,6,16,6,6),state_length=c(50,22,12,22,12,50),wrap=FALSE)+

ease_aes('sine-in-out')+

exit_fade()+enter_fade()

animate(p,nframes=175)

Simulated data

n <- 5000

b.true <- 5.25

iv.dat <- tibble(

z = rnorm(n,0,2),

eps = rnorm(n,0,1),

d = (z + 1.5*eps + rnorm(n,0,1) >0.25),

y = 2.5 + b.true*d + eps + rnorm(n,0,0.5)

)- endogenous

eps: affects treatment and outcome zis an instrument: affects treatment but no direct effect on outcome

Results with simulated data

Recall that the true treatment effect is 5.25

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ d, data = iv.dat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-3.6842 -0.6864 -0.0033 0.6899 4.3910

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 2.08624 0.01986 105.1 <2e-16 ***

dTRUE 6.15766 0.02915 211.2 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 1.028 on 4998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.8993, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8992

F-statistic: 4.462e+04 on 1 and 4998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16TSLS estimation - Dep. Var.: y

Endo. : d

Instr. : z

Second stage: Dep. Var.: y

Observations: 5,000

Standard-errors: IID

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 2.50612 0.029812 84.0643 < 2.2e-16 ***

fit_dTRUE 5.25274 0.054380 96.5941 < 2.2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

RMSE: 1.12249 Adj. R2: 0.879822

F-test (1st stage), dTRUE: stat = 2,606.7, p < 2.2e-16, on 1 and 4,998 DoF.

Wu-Hausman: stat = 558.7, p < 2.2e-16, on 1 and 4,997 DoF.Two-stage equivalence

R Code

step1 <- lm(d ~ z, data=iv.dat)

d.hat <- predict(step1)

step2 <- lm(y ~ d.hat, data=iv.dat)

summary(step2)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ d.hat, data = iv.dat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-8.2540 -2.1816 -0.1687 2.2333 10.7230

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 2.50612 0.07575 33.09 <2e-16 ***

d.hat 5.25274 0.13817 38.02 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 2.853 on 4998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.2243, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2242

F-statistic: 1445 on 1 and 4998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Assumptions of IV

Key IV assumptions

- Exclusion: Instrument is uncorrelated with the error term

- Validity: Instrument is correlated with the endogenous variable

- Monotonicity: Treatment more (less) likely for those with higher (lower) values of the instrument

Assumptions 1 and 2 sometimes grouped into an only through condition.

Checking instrument

Bare minimum (probably not even that) is to check first stage and reduced form:

- Check the ‘first stage’

Call:

lm(formula = d ~ z, data = iv.dat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.06484 -0.33153 -0.02397 0.34092 1.40327

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 0.462255 0.005719 80.83 <2e-16 ***

z 0.144829 0.002837 51.06 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.4044 on 4998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.3428, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3426

F-statistic: 2607 on 1 and 4998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16- Check the ‘reduced form’

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ z, data = iv.dat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-8.2540 -2.1816 -0.1687 2.2333 10.7230

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 4.93423 0.04034 122.31 <2e-16 ***

z 0.76075 0.02001 38.02 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 2.853 on 4998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.2243, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2242

F-statistic: 1445 on 1 and 4998 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Do we need IV?

- Let’s run an “augmented regression” to see if our OLS results are sufficiently different than IV

R Code

d.iv <- lm(d ~ z, data=iv.dat)

d.resid <- residuals(d.iv)

haus.test <- lm(y ~ d + d.resid, data=iv.dat)

summary(haus.test)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ d + d.resid, data = iv.dat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-3.3708 -0.6429 -0.0112 0.6636 4.1932

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 2.50612 0.02589 96.80 <2e-16 ***

dTRUE 5.25274 0.04723 111.22 <2e-16 ***

d.resid 1.37689 0.05825 23.64 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.975 on 4997 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9094, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9094

F-statistic: 2.508e+04 on 2 and 4997 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16- Test for significance of

d.residsuggests OLS is inconsistent in this case

Testing exclusion

- Exclusion restriction says that your instrument does not directly affect your outcome

- Potential testing ideas:

- “zero-first-stage” (subsample on which you know the instrument does not affect the endogenous variable)

- augmented regression of reduced-form effect with subset of instruments (overidentified models only)

- Sargan or Hansen’s J test (null hypothesis is that instruments are uncorrelated with residuals)

Kippersluis and Rietveld (2018), “Beyond Plausibly Exogenous”

- “zero-first-stage” test

- Focus on subsample for which your instrument is not correlated with the endogenous variable of interest

- Regress the outcome on all covariates and the instruments among this subsample

- Coefficient on the instruments captures any potential direct effect of the instruments on the outcome (since the correlation with the endogenous variable is 0 by assumption).

Beckert (2020), “A Note on Specification Testing…”

With at least \(n\) valid instruments, test if all instruments are valid against the alternative that up to \(m - n\) instruments are valid

- Estimate the first-stage regressions and save residuals, denoted \(\hat{u}\).

- Estimate the “artificial” regression \[y=\beta x + \delta \tilde{z} + \gamma \hat{u} + \varepsilon\] where \(\tilde{z}\) denotes a subset of \(m-n\) instruments from the full instrument matrix \(z\).

- Test the null that \(\delta=0\) using a standard F-test

Solving an Exclusion Problem

Conley, Hansen, and Rossi (2012) and “plausible exogeneity”, union of confidence intervals approach:

- Suppose extent of violation is known in \(y_{i} = \beta x_{i} + \gamma z_{i} + \varepsilon_{i}\), so that \(\gamma = \gamma_{0}\)

- IV/TSLS applied to \(y_{i} - \gamma_{0}z_{i} = \beta x_{i} + \varepsilon_{i}\) works

- With \(\gamma_{0}\) unknown…do this a bunch of times!

- Pick \(\gamma=\gamma^{b}\) for \(b=1,...,B\)

- Obtain \((1-\alpha)\) % confidence interval for \(\beta\), denoted \(CI^{b}(1-\alpha)\)

- Compute final CI as the union of all \(CI^{b}\)

Solving an Exclusion Problem

Nevo and Rosen (2012):

\[y_{i} = \beta x_{i} + \delta D_{i} + \varepsilon_{i}\]

- Allow instrument, \(z\), to be correlated with \(\varepsilon\), but \(|\rho_{x, \varepsilon}| \geq |\rho_{z, \varepsilon}|\)

- i.e., IV is better than just using the endogenous variable

- Assume \(\rho_{x, \varepsilon} \times \rho_{z, \varepsilon} >0\) (same sign of correlation in the error)

- Denote \(\lambda = \frac{\rho_{z, \varepsilon}}{\rho_{x, \varepsilon}}\), then valid \(IV\) would be \(V(z) = \sigma_{x} z - \lambda \sigma_{z} x\)

- Can bound \(\beta\) using range of \(\lambda\)

Instrument Validity

Just says that your instrument is correlated with the endogenous variable, but what about the strength of the correlation?

Why we care about instrument strength

Recall our schooling and wages equation, \[y = \beta S + \epsilon.\] Bias in IV can be represented as:

\[Bias_{IV} \approx \frac{Cov(S, \epsilon)}{V(S)} \frac{1}{F+1} = Bias_{OLS} \frac{1}{F+1}\]

- Bias in IV may be close to OLS, depending on instrument strength

- Bigger problem: Bias could be bigger than OLS if exclusion restriction not fully satisfied

Testing strength of instruments

Two things going on simultaneously:

- Strength of the first-stage

- Inference on coefficient of interest in the structural equation

Applied researchers tend to (wrongly) think of these as separate issues.

Testing strength of instruments

Many endogenous variables

- Stock and Yogo (2005) test based on Cragg & Donald statistic (homoskedasticity only)

- Kleibergen and Paap (2006) Wald statistic

- Sanderson and Windmeijer (2016) extension

- Effective F-statistic from Olea and Pflueger (2013) (as approximation)

Testing strength of instruments

Single endogenous variable

- Partial \(R^{2}\) (never see this)

- Stock and Yogo (2005) test based on first-stage F-stat (homoskedasticity only)

- Critical values in tables, based on number of instruments

- Rule-of-thumb of 10 with single instrument (higher with more instruments)

- Lee et al. (2021): With first-stage F-stat of 10, standard “95% confidence interval” for second stage is really an 85% confidence interval

Testing strength of instruments

Single endogenous variable

- Partial \(R^{2}\) (never see this)

- Stock and Yogo (2005) test based on first-stage F-stat (homoskedasticity only)

- Kleibergen and Paap (2006) Wald statistic

- Effective F-statistic from Olea and Pflueger (2013)

Testing strength of instruments

Single endogenous variable

- Inference with Anderson-Rubin CIs (homoskedastic)

- Inference with Lee et al. (2021) tables (allows for more general error structure)

Testing strength of instruments: First-stage

Single endogenous variable

- Homoskedasticity: Stock & Yogo, effective F-stat

- Heteroskedasticity: Effective F-stat

Many endogenous variables

- Homoskedasticity: Stock & Yogo with Cragg & Donald statistic, Sanderson and Windmeijer (2016), effective F-stat from Olea and Pflueger (2013)

- Heteroskedasticity: Kleibergen & Papp (Kleibergen and Paap (2006)) Wald is robust analog of Cragg & Donald statistic, effective F-stat from Olea and Pflueger (2013)

Testing strength of instruments: Inference

Single endogenous variable

Many endogenous variables

- Homoskedasticity: Projection-based confidence sets using the Anderson-Rubin CI (Dufour & Taamouti, 2005) but low power

- Heteroskedasticity: Go figure it out!

Making sense of all of this…

- Test first-stage using effective F-stat

- Present weak-instrument-robust inference using Anderson-Rubin CIs or Lee tF tests

Many endogenous variables problematic because strength of instruments for one variable need not imply strength of instruments for others

Interpreting Instrumental Variables Results

Heterogenous TEs

- In constant treatment effects, \(Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0) = \delta_{i} = \delta, \text{ } \forall i\)

- Heterogeneous effects, \(\delta_{i} \neq \delta\)

- With IV, what parameter did we just estimate? Need monotonicity assumption to answer this

Monotonicity

Assumption: Denote the effect of our instrument on treatment by \(\pi_{1i}\). Monotonicity states that \(\pi_{1i} \geq 0\) or \(\pi_{1i} \leq 0, \text{ } \forall i\).

- Allows for \(\pi_{1i}=0\) (no effect on treatment for some people)

- All those affected by the instrument are affected in the same “direction”

- With heterogeneous ATE and monotonicity assumption, IV provides a “Local Average Treatment Effect” (LATE)

LATE and IV Interpretation

- LATE is the effect of treatment among those affected by the instrument (compliers only).

- Recall original Wald estimator:

\[\delta_{IV} = \frac{E[Y_{i} | Z_{i}=1] - E[Y_{i} | Z_{i}=0]}{E[D_{i} | Z_{i}=1] - E[D_{i} | Z_{i}=0]}=E[Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0) | \text{complier}]\]

- Practically, monotonicity assumes there are no defiers and restricts us to learning only about compliers

Is LATE meaningful?

- Learn about average treatment effect for compliers

- Different estimates for different compliers

- IV based on merit scholarships

- IV based on financial aid

- Same compliers? Probably not

LATE with defiers

- In presence of defiers, IV estimates a weighted difference between effect on compliers and defiers (in general)

- LATE can be restored if subgroup of compliers accounts for the same percentage as defiers and has same LATE

- Offsetting behavior of compliers and defiers, so that remaining compliers dictate LATE

Marginal Treatment Effects

- Lots of different treatment effects…ATT, ATU, LATE

- Would be nice to have full distribution, \(f(\delta-{i})\), from which we could derive ATE, ATT, LATE, etc.

- Marginal treatment effect (MTE) is nonparametric function that links all of these together

- Treatment effect, \(\delta_{i} = Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0)\)

- Treatment governed by index, \(D_{i} = \mathbb{1}(\gamma z_{i} \geq v_{i})\), with instruments \(z\)

\[\delta^{MTE} (x, v_{i}) = E[\delta_{i} | x_{i} = x, \gamma z_{i} = v_{i}]\]

Marginal Treatment Effects

\[\delta^{MTE} (x, v_{i}) = E[\delta_{i} | x_{i} = x, \gamma z_{i}=v_{i}]\]

- \(\gamma z_{i} = v_{i}\) captures indifference between treatment and no treatment

- Instead of number (like ATT or LATE), \(\delta^{MTE}(x,v)\) is a function of \(v\)

- Average effect of treatment for everyone with the same \(\gamma z_{i}\)

Marginal Treatment Effects

What is \(\gamma z_{i}\)?

For any single index model: \[D_{i} = \mathbb{1}(\gamma z_{i} \geq v_{i}) = \mathbb{1}(u_{is} \leq F(\gamma z_{i})) \text{ for } u_{is} \in [0,1]\]

- \(F(\gamma z_{i})\) is CDF of \(v{i}\)

- Inverse CDF transform to translate into uniform distribution

- Yields propensity score, \(P(z_{i}) = Pr(D_{i}=1 | z_{i}) = F(\gamma z_{i})\) (ranking all units according to probability of treatment)

Marginal Treatment Effects

- MTE is LATE as change in \(z\) approaches 0 (Heckman, 1997)

- MTE is Local IV:

\[\delta^{LIV} (x,p) = \frac{\partial E[Y | x, P(z)=p]}{\partial p}\]

- How does outcome \(Y_{i}\) change as we push one more person into treatment

Derivation

\[\begin{eqnarray*} Y(0) &=& \gamma_0 x + u_0\\ Y(1) &=& \gamma_1 x + u_1 \end{eqnarray*}\]

\(P(D=1 | z) = P(z)\) works as our instrument with two assumptions:

- \((u_0, u_1, u_s) \perp P(z) | x\). (Exogeneity)

- Conditional on \(z\) there is enough variation in \(z\) for \(P(z)\) to take on all values \(\in(0,1)\).

- Much stronger than typical validity assumption, akin to special regressor in Lewbel’s work

- Binary variable, \(D=\mathbb{1}(V+W^{*}\geq 0)\). “If \(V\) is independent of \(W\), then variation in \(V\) changes the probability of \(D=1\) in such a way that traces out the distribution of \(W^{*}\)

Derivation

Now we can write, \[\small \begin{eqnarray*} Y &=& \gamma_0' x + D(\gamma_1 - \gamma_0)' x + u_0 + D(u_1 - u_0)\\ E[Y| x,P(z)=p] &=& \gamma_0' x + p(\gamma_1 - \gamma_0)'x + E[D(u_1 - u_0)|x,P(z)=p] \end{eqnarray*}\]

Observe \(D=1\) over the interval \(u_s = [0,p]\) and zero for higher values of \(u_s\). Let \(u_1-u_0 \equiv \eta\). \[\small \begin{eqnarray*} E[D(u_1 - u_0) | P(z) =p,x] &=& \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{0}^{p} (u_1 - u_0) f((u_1-u_0) | u_s) d u_s d(u_1 -u_0)\\ E[D(\eta) | P(z) =p,x] &=& \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{0}^{p} \eta f(\eta | u_s) d\, \eta d\, u_s\\ \end{eqnarray*}\]

Derivation

Recall: \[\begin{align*} E[Y| x,P(z)=p] &= \gamma_0' X + p(\gamma_1 - \gamma_0)'X + E[D(u_1 - u_0)|x,P(z)=p]\\ \end{align*}\]

And the derivative: \[\begin{align*} \delta^{MTE}(p) = \frac{\partial E[Y | x, P(z)=p]}{\partial p} &= (\gamma_1 - \gamma_0)'x + \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \eta f(\eta | u_s =p) d\, \eta\\ &= \underbrace{(\gamma_1 - \gamma_0)'x}_{ATE(x)}+ E[\eta | u_s =p] \end{align*}\]

What is \(E[\eta | u_s =p]\)? The expected unobserved gain from treatment of those people who are on the treatment/no-treatment margin \(P(z)=p\).

MTE to ATE

Calculate the outcome given \((x,z)\) (actually \(z\) and \(P(z)=p\)).

\[\begin{align*} \delta^{ATE}(x, T=1)&=E\left(\delta^{MTE} | X=x \right)\\ \end{align*}\]

ATE: We treat everyone. \[\begin{eqnarray*} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \delta^{MTE}(p) = (\gamma_1 - \gamma_0)'x + \underbrace{\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} E(\eta | u_s) d\, u_s}_{0} \end{eqnarray*}\]

MTE to ATT

Calculate the outcome given \((x,z)\) (actually \(z\) and \(P(z)=p\)).

\[\begin{align*} \delta^{ATT}(x, P(z), T=1)&=E\left(\delta^{MTE} | X=x, u_{s} \leq P(z)\right)\\ \end{align*}\]

ATT: Treat only those with a large enough propensity score \(P(z)>p\): \[\begin{eqnarray*} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \delta^{MTE}(p,x) \frac{Pr(P(z | x) > p)}{E[P(z | x)]} d\,p \end{eqnarray*}\]

MTE to LATE

Calculate the outcome given \((x,z)\) (actually \(z\) and \(P(z)=p\)).

\[\begin{align*} \delta^{L A T E}\left(x, P(z), P\left(z^{\prime}\right)\right)&=E\left(\delta^{MTE} | X=x, P\left(z^{\prime}\right) \leq u_s \leq P(z)\right) \end{align*}\]

LATE: Integrate over the compliers: \[\begin{eqnarray*} LATE(x,z,z')= \frac{1}{P(z) - P(z')} \int_{P(z')}^{P(z)} \delta^{MTE}(p,x) \end{eqnarray*}\]

MTE to OLS and IV

This is harder… \[\begin{align*} w^{I V}\left(u_{s}\right)=\left[E\left(P(z) | P(z)>u_{s}\right)-E(P(z))\right] \frac{E(P(z))}{\operatorname{Var}(P(z))}\\ w^{O L S}\left(u_{s}\right)=1+\frac{E\left(u_{1} | u_{s}\right) h_{1}-E\left(u_{0} | u_{s}\right) h_{0}}{\delta^{M T E}\left(u_{s}\right)}\\ h_{1}=\frac{E\left(P(z) | P(z)>u_{s}\right)}{ E(P(z))}, \quad h_{0}=\frac{E\left(P(z) | P(z)<u_{s}\right)}{E(P(z))} \end{align*}\]

MTE in practice

- Estimate \(P(z)= Pr(D=1 | z)\) nonparametrically (\(z\) includes instruments and all exogenous \(x\) variables)

- Flexible/nonparametric regression of \(Y\) on \(x\) and \(P(z)\)

- Differentiate w.r.t. \(P(z)\)

- Plot for all values of \(P(z)=p\)

As long as \(P(z)\) covers \((0,1)\), we can trace out the full distribution of \(\delta^{MTE}(p)\)

Example

- Idea: what is the effect of detailing in prescription drugs (statins)

- IV: Restrictions on detailing from conflict-of-interest policies imposed by large Academic Medical Centers…spillover to other hospitals

- Estimate MTE and examine welfare effects in structural framework

Common IV Designs Today

Judge Fixed Effects

- Many different possible decision makers

- Individuals randomly assigned to one decision maker

- Decision makers differ in leniency of assigning treatment

- Common in crime studies due to random assignment of judges to defendants

Judge Fixed Effects

Aizer and Doyle (2015), QJE, “Juvenile Incarceration, Human Capital, and Future Crime: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Judges”

- Proposed instrument: propensity to convict by the judge

- Idea: judge has some fixed leniency, and random assignment into judges introduces exogenous variation in probability of conviction

- In practice: judge assignment isn’t truly random, but it is plausibly exogenous

Judge Fixed Effects

Constructing the instrument:

- Leave-one-out mean \[z_{j} = \frac{1}{n_{j} - 1} \sum_{k \neq i}^{n_{j}-1} JI_{k}\]

- This is the mean of incarceration rates for judge \(j\) when excluding the current defendant, \(i\)

- Could also residualize \(JI_{k}\) (remove effects due to day of week, month, etc.)

Judge Fixed Effects

- Common design: possible in settings where some influential decision-makers exercise discretion and where individuals can’t control the match

- Practical issue: Use jackknife IV (JIVE) to “fix” small-sample bias

- JIVE more general than judge fixed effects design

- Idea: estimate first-stage without observation \(i\), use coefficients for predicted endogeneous variable for observation \(i\), repeat

- May improve finite-sample bias but also loses efficiency

- Biggest threat: monotonicity…judges may be more/less lenient in different situations or for different defendants

Bartik Instruments

Decompose observed growth rate into:

- “Share” (what extra growth would have occurred if each industry in an area grew at their industry national average)

- “Shift” (extra growth due to differential growth locally versus nationally)

Bartik Instruments

- Want to estimate \[y_{l} = \alpha + \delta I_{l} + \beta w_{l} + \varepsilon_{l}\] for location \(l\) (possibly time \(t\) as well)

- \(I_{l}\) reflect immigration flows

- \(w_{l}\) captures other observables and region/time fixed effects

Bartik Instruments

Instrument:

\[B_{l} = \sum_{k=1}^{K} z_{l,k} \Delta_{k},\]

- \(l\) denotes market location (e.g., Atlanta), country, etc. (wherever flows are coming into)

- \(k\) reflects the source country (where flows are coming out)

- \(z_{lk}\) denotes the share of immigrants from source \(k\) in location \(l\) (in a base period)

- \(\Delta_{k}\) denotes the shift (i.e., change) from source country into the destination country as a whole (e.g., immigration into the U.S.)

Other Examples

\[\begin{align} B_{l} &= \sum_{k=1}^{K} z_{lk} \Delta_{k},\\ \Delta_{lk} &= \Delta_{k} + \tilde{\Delta_{lk}} \end{align}\]

China shock Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (2013):

- \(z_{lk}\): location, \(l\), and industry, \(k\), composition

- \(\Delta_{lk}\): location, \(l\), and industry, \(k\), growth in imports from China

- \(\Delta_{k}\): industry \(k\) growth of imports from China

Other Examples

\[\begin{align} B_{l} &= \sum_{k=1}^{K} z_{lk} \Delta_{k},\\ \Delta_{lk} &= \Delta_{k} + \tilde{\Delta_{lk}} \end{align}\]

Immigrant enclave (Altonji and Card, 1991):

- \(z_{lk}\): share of people from foreign country \(k\) living in current location \(l\) (in base period)

- \(\Delta_{lk}\): growth in the number of people from \(k\) to \(l\)

- \(\Delta_{k}\): growth in people from \(k\) nationally

Other Examples

\[\begin{align} B_{l} &= \sum_{k=1}^{K} z_{lk} \Delta_{k},\\ \Delta_{lk} &= \Delta_{k} + \tilde{\Delta_{lk}} \end{align}\]

Market size and demography (Acemoglu and Linn, 2004):

- \(z_{lk}\): spending share on drug \(l\) from age group \(k\)

- \(\Delta_{lk}\): growth in spending of group \(k\) on drug \(l\)

- \(\Delta_{k}\): national growth in spending of group \(k\) (e.g., due to population aging)

Bartik Instruments

- Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift (2020) show that using \(B_{l}\) as an instrument is equivalent to using local industry shares, \(z_{lk}\), as IVs

- Can decompose Bartik-style IV estimates into weighted combination of estimates where each share is an instrument (Rotemberg weights)

- Borusyak, Hull, and Jaravel (2021), ReStud, instead focus on situation in which the shifts are exogenous and the shares are potentially endogenous

- Borusyak and Hull (2023), Econometrica, provide general approach when using exogenous shifts (recentering as in empirical exercise)

key: literature was vague as to the underlying source of variation in the instrument…recent papers help in understanding this (and thus defending your strategy)